There were no performers who possessed more talent than singer-songwriter Nanci Griffith in the 1980s and early ’90s, when she was at her remarkable best.

By Daniel Gewertz

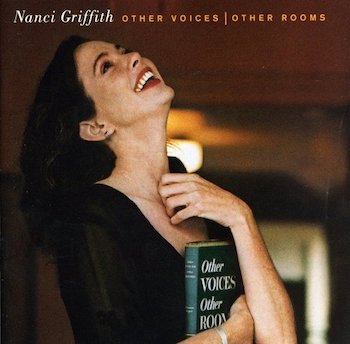

Nanci Griffith, the Texan “folkabilly” singer-songwriter, died in August at the age of 68, after fighting two different cancers for 25 years. In my decades of writing about contemporary folk music, I’d venture to say there were no performers who possessed more talent than Griffith in the 1980s and early ’90s, when she was at her remarkable best. Her single Grammy win was in the Contemporary Folk category, for Other Voices, Other Rooms, a guest-star-laden 1993 project of folk gems written by others. That she never won a Grammy for any of her own compositions is an injustice. She was both a stunning songwriter and a savvy song-finder. And as a singer, she gave “precious” a good name.

Boston took to Griffith earlier and stronger than any American city outside her native Texas. I got to interview her for the Boston Herald many times, starting right before she signed with the locally based Philo/Rounder Records in 1984; I felt I knew Griffith as well as a Northern journalist could. She was a tightly wound tumble of conflicting instincts: both forthright and private, both steely and prickly, proud of her achievements and openly hurt that she was not more widely rewarded for them. I saw a lot of gigs, many of them solo. But there was a single show in the mid-’80s that best displayed Griffith’s indomitable strength. It was at the Harvard Square basement room then called Passim Coffeehouse.

Let me set the scene. The late Bob Donlin was introducing her from the tiny Passim stage in his usual charming yet wooden way. Nanci was standing still in the back of the tightly packed little club, aware that most eyes were already upon her.

At the utterance of her name, she stepped forward with resolute energy. But she had forgotten there were two brick steps at the edge of the seating area. She pitched violently forward, landing on hands and knees, almost prone. The crowd emitted a collective gasp. But Nanci jumped up and darted purposefully to the stage. She laughed, said something self-deprecating about her innate awkwardness, and then launched into one of her favorite upbeat songs full force, her energy perfectly focused. There were no further comments in the hour-long set about the mishap. It was a great show. Only days later did we hear that Griffith had suffered bruises to both skin and bone, and was seen at a local hospital.

That was Nanci Griffith: more or less equal parts gumption and vulnerability; a force of nature and a delicate, worried soul. She was a waiflike Texas sweetheart at first glance, but while the simple word “heart” was one of her favorites as a writer, Griffith’s own heart was, in interviews, often hidden. She was almost as likely to complain about slights as exhibit contentment. But one thing you could always expect: fierce affection for her talented musical friends and band-members.

Nanci Caroline Griffith was born on July 6, 1953, in Seguin, TX; the family moved to Austin soon afterward. She began singing at Austin open-mic nights at age 12, brought to the bars by her father. For a short spell in her early 20s she was a schoolteacher, but music called her. By 24 she had recorded her first LP for a tiny label, Featherbed. There was an early marriage and divorce, to a fellow Texan singer-songwriter, Eric Taylor, a Vietnam veteran and heroin addict. They later became friends.

I am not alone in thinking that Griffith’s best LPs were the two she did on the Philo/Rounder label in the mid-’80s, Once in a Very Blue Moon (1984) and Last of the True Believers (1986), both produced by folk-legend Jim Rooney. The musicians were mostly little known at the time. Now is a different story. Among the players and singers: Bela Fleck, Mark O’Connor, Lyle Lovett, Roy Husky Jr., Lloyd Green, Pat Alger, Robert Earl Keen, Tom Russell and Maura O’Connell.

A group photo in the CD booklet of Very Blue Moon shows Rooney and all the musicians and engineers at Jack Clement’s Cowboy Arms Hotel & Recording Spa. Taken beside a swimming pool, the photo is captioned “The Once in a Very Blue Moon Sink or Swim Team,” and the baker’s dozen of guys and gals assembled in shorts, jeans, and swim-trunks were obviously a loose, happy bunch. From that point on, Griffith named every band she fronted, big or small, The Blue Moon Orchestra. The clear desire, I assume, was to honor and recall that album’s familial spirit. The core of the band stayed with her for the long haul.

Essentially that same group created Last of the True Believers, in 1986, another graceful merging of folk and country, revved up by bluegrass fast-picking wizardry. That album copped a Grammy nomination, and “won” Nanci Griffith a contract at MCA Records, a big label in Nashville. It is no accident I put the word won in quotes, for the move to MCA, in my opinion, ultimately diminished Griffith’s career. MCA was signing a lot of new talent willy-nilly back in the late ’80s. (The Nashville industry joke at the time was that MCA stood for “More Crummy Artists.”) Griffith told me, and others, that the label didn’t know what to do with her. Yet her first two albums didn’t muck up the basic Griffith sound. It was Nanci herself who coined the term folkabilly, the merging of folk and rockabilly. It’s a pretty fair term. Griffith always had two distinct voices, her exceedingly high, delicate ballad voice, and the gutsy, mid-range crowing that she unleashed for life-affirming uptempo numbers. They seemed to almost come from two different people, those two voices, and it is not surprising that her country radio audience did not cotton to them.

“The radio person at MCA Nashville told me that I would never be on radio because my voice hurt people’s ears,” Griffith told me once, and she told it to a lot of journalists. She was hurt.

She actually didn’t do badly for MCA. She had a couple of singles in the country Top 40, and her first two albums made it above the #30 mark. That wasn’t good enough for the label, though: they wanted a full-stop radio star. I don’t think that her failure to achieve adulation from the country music audience was about Griffith’s very high voice: it was about her lack of traditional sexiness, or even traditional “womanliness.” Nanci might’ve been the darling of the blue state folk circuit, but on country radio she was a sad-voiced skinny girl without a whit of sex appeal. And she was no good ol’ girl, either.

There was a brief period in the late ’80s when the Nashville-centered country music industry flirted with a wider artistic palette. Steve Earle called it, with biting wit, “country music’s great credibility scare.” By 1990 it was nearly over, and MCA farmed Griffith out to their pop division. That meant MOR, Middle of the Road. She was suddenly a rootsy poet wandering among the synthesizers. Ghost is a favorite word in Griffith’s lyrics, but it was her later years at MCA that really might have spooked her. On a few later albums she vacillated between her natural balladic voice and an oddly pretentious vocal approach that sounded like a cloying little girl.

Her next label, Elektra, brought about two triumphs: her Grammy-winning Other Voices, Other Rooms (named after the Truman Capote novel) and The Dust Bowl Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra. But ultimately, her great victories in life weren’t about awards, label deals, or Top 40s. It is about the dozens of fine songs — many of them little short stories in concise song-form. A few were hits for other singers, such as “Love at the Five & Dime” and “Listen to the Radio” (Kathy Mattea) and “Outbound Plane” (Suzy Boggus). “Gulf Coast Highway,” “I Wish It Would Rain” and the sublime Dust Bowl ballad “Trouble in the Fields” were sung by many, including Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris. And then there’s the remarkable “It’s a Hard Life Wherever You Go,” which bounds between Dublin and Chicago, the present and the past, to show that “If we poison our children with hatred / Then the hard life is all that they’ll know.” That one was even done by Cher.

Her next label, Elektra, brought about two triumphs: her Grammy-winning Other Voices, Other Rooms (named after the Truman Capote novel) and The Dust Bowl Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra. But ultimately, her great victories in life weren’t about awards, label deals, or Top 40s. It is about the dozens of fine songs — many of them little short stories in concise song-form. A few were hits for other singers, such as “Love at the Five & Dime” and “Listen to the Radio” (Kathy Mattea) and “Outbound Plane” (Suzy Boggus). “Gulf Coast Highway,” “I Wish It Would Rain” and the sublime Dust Bowl ballad “Trouble in the Fields” were sung by many, including Willie Nelson and Emmylou Harris. And then there’s the remarkable “It’s a Hard Life Wherever You Go,” which bounds between Dublin and Chicago, the present and the past, to show that “If we poison our children with hatred / Then the hard life is all that they’ll know.” That one was even done by Cher.

Her love songs often struck an honest yet wistful tone, at times unusual in phrasing and the pattern of thoughts. But it was her story-songs — inspired by such favorite Southern writers as Capote, Carson McCullers, and Tennessee Williams — that employed striking narrative choices. None were bolder than “Mary & Omie,” a song she chose to sing in the first person as a middle-aged Black woman whose loving husband moved the family north and fought for a middle-class existence “because Omie wouldn’t settle for less.”

Considering her battle with two cancers, her lack of recent albums, and her bitterness over her pursuit of mainstream success, it is possible to paint a melancholy personal picture of Griffith in her later years. While her story-songs about other people remained hopeful, her personal songs of loneliness and brief love affairs became less poignant and enchanting as the years progressed. In the old days, her songs could break your heart and mend it again. Some later ones merely emitted frustrated sadness. But there is grace to be found even in those weaker works. After all, the courage to sing about the neurotic feelings of the heart is uncommon. She left a large body of notable work. There is no better testament to her talent than the 84-minute concert film Winter Marquee, recorded in Knoxville in 2002 (available on YouTube).

It shows Griffith not only in prime form, at 49, but also fronting a phenomenally talented version of her long-lasting Blue Moon Orchestra. The communal feeling of her early albums is evident. The live CD version of the concert also finds Griffith back on her old label, Rounder.

I was delighted she chose to revive one of my favorite songs from her 1984 Blue Moon album, “I’m Not Drivin’ These Wheels.” For starters, it takes place in Massachusetts, on a bus ride Nanci took from Boston to Marshfield to be interviewed by Dick Pleasants on WATD. As in many of her songs, the lyrics have odd little jumps in logic and narrative that force the listener to fill in the blanks. So when the chorus goes “Bring the prose to the wheel / I’m not driving these wheels,” she is singing of the wheels of literary inspiration as well as the wheels of the bus she rides, and the word prose refers to the book in her lap as well as the song lyrics she is beginning to dream up. She sounds positively exultant that the creative forces come from outside herself.

So many of her compositions reveal her own life, lived alone. On the great song “Daddy Said,” the titular character advises, “You’ll never learn to fish on a borrowed line / you’ll never learn to write if you’re walkin’ round cryin’ / And it’s a pity your lover died young / but you’ll never get tired of living alone.”

That may have proven true of Griffith’s hit-and-miss romantic life. But her real love life was with her musicians and friends, and that life lasted. The Winter Marquee show feels like something more than a superb concert: it is a career benediction. Near its end, Griffith brings out a surprise guest — Emmylou Harris, a good friend. Harris walks up to the mic with a grin as wide as it is authentic. “I just have one thing to say,” she announces, looking at her friend. “Isn’t she lovely?”

She was.

For 30 years, Daniel Gewertz wrote about music, theater and movies for the Boston Herald, among other periodicals. More recently, he’s published personal essays, taught memoir writing, and participated in the local storytelling scene. In the 1970s, at Boston University, he was best known for his Elvis Presley imitation.

Source: Music Remembrance: Singer-songwriter Nanci Griffith (1953-2021) – The Arts Fuse