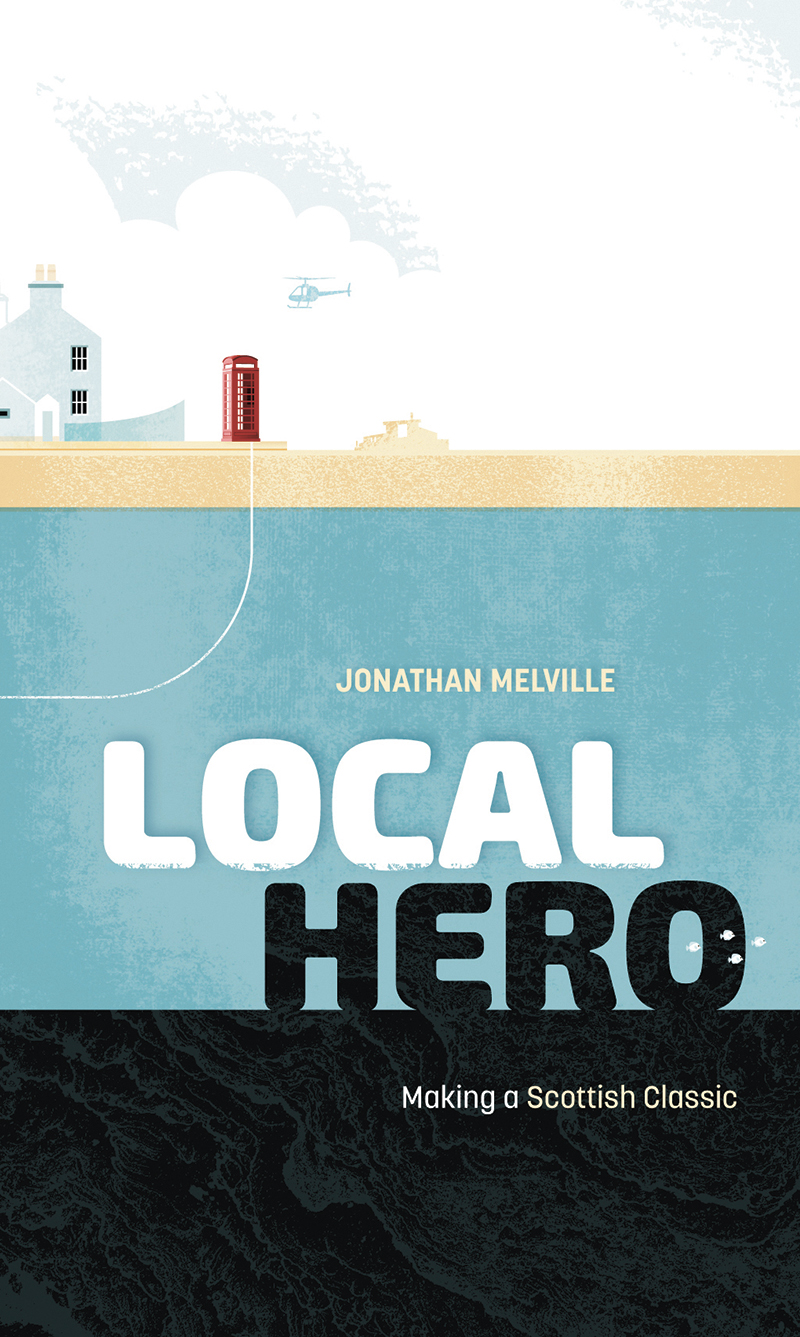

Superfan Jonathan Melville takes an in-depth look at the legendary Scottish comedy-drama movie as it’s 40th anniversary approaches

By Jonathan Melville

“It’s not a high-concept movie, there’s actually no story there really. It’s what happens in between the story that’s important.” The words of filmmaker Bill Forsyth, spoken to me on a rainy night in Mallaig in 2013 after a screening of the then 30-year-old Local Hero, lodged in my mind and refused to budge.

Fast forward a decade and I’ve just finished writing a book examining the evolution of the concept that would go on to become one of Scotland’s best-loved exports, adored around the globe and with famous fans including Top Gun: Maverick producer Jerry Bruckheimer. The key word here is ‘evolution’, as the idea for the film that follows Texan oilman “Mac” MacIntyre (Peter Riegert), sent to buy the Scottish village of Ferness so that it can be turned into an oil refinery, took various twists and turns that I felt deserved documenting as the 40th anniversary approaches.

It’s tricky to pinpoint a single moment that could be said to be the birth of Local Hero, though one could plump for a chance meeting between writer-director Bill Forsyth and David Puttnam, producer of the future Oscar-winning Chariots of Fire, in a Soho tobacconist’s shop in 1980. The pair had first met a year earlier when Forsyth, fresh from the success of his first zero-budget Scottish film, That Sinking Feeling, tried to interest Puttnam in producing Gregory’s Girl, only for the producer to turn him down and leave the young Scot to find the funding himself.

When their paths crossed again, Puttnam had the kernel of an idea set against the backdrop of the Scottish oil industry, which had hit the headlines in the early ’70s when oil was found 100 miles northeast of Shetland’s capital, Lerwick. News of the deal secured by Shetland Islands Council, which ensured special funds were set up for the benefit of the area’s residents, sparked Puttnam’s interest. It led him to pitch the idea to Forsyth, who initially thought that a Scottish hotelier would be the local hero of the title, out-negotiating the oil company in a series of thrilling sequences. He soon jettisoned the thriller aspects, upped the comedy quotient, kept the title and focused on an American oil man.

Most fans are aware that Local Hero’s original ending was hastily reworked at the insistence of nervous studio executives who feared leaving audiences on a downbeat note. But it was only once I spoke to members of the cast and crew, starting with Forsyth in 2013, and read early drafts of the script that I realised how much wasn’t yet known.

Riegert explained just how much he wanted to secure the role over other contenders Michael Douglas and Henry Winkler. John Gordon-Sinclair (rogue motorcyclist Ricky) told how he and Peter Capaldi (Danny Oldsen) rehearsed beach landings between takes in the spring of 1982, fearful they’d be called up to fight in the Falklands War. I also heard how Chariots of Fire winning an Oscar led to skyrocketing fees for filming in empty fields.

Then there were the deleted scenes revealed in Forsyth’s hand-annotated early scripts, each one filmed and then discarded for time or logic reasons. With a longer sequence set in the mist after Mac and Danny hit poor Trudy, more discussion about mermaids than ended up in the finished film, an extremely dark moment on the beach, and Mac and Oldsen keeping their mission secret from the locals, there was more to the film than I’d ever imagined.

There’s no single thing that makes Local Hero my favourite Scottish film, just a seemingly effortless blend of humour, casting and locations that, as the book hopefully shows, weren’t entirely effortless. Bill Forsyth doesn’t shy away from raising complex issues, pointing out the bad things happening around Mac and the villagers who are willing to see their livelihoods and homes destroyed in exchange for a few million pounds, but he does it in a way that isn’t heavy-handed and still leaves space for magical moments.

On a pilgrimage to Pennan [where the film was shot] earlier this year I was impressed by how little had changed, though there are now fewer residents and more holiday homes. Locals are proud of their place in film history, but they don’t fetishise the past and they’re happy to welcome surf enthusiasts and tourists as long as they’re allowed some space for themselves.

If it’s what happens between the story that’s important in Local Hero, then my hope is that this book will reveal what happened in between those moments to ensure a classic was made over the course of a few months in 1982. With any luck, fans will view the film with fresh eyes the next time they visit Ferness.

Local Hero: Making a Scottish Classic by Jonathan Melville is out now (Polaris, £17.99). You can buy from The Big Issue shop on Bookshop.org, which helps to support The Big Issue and independent bookshops.

Source: Author Jonathan Melville: My trip behind the scenes of classic movie Local Hero – The Big Issue