By Liam Ward

Before rock and roll would sweep through the landscape and the consciousness of the youth, a forgotten musical genre held a nation in its grip. A rhythmic, urgent music of expression and movement that was simple and accessible due to the addition of improvised homemade instrumentation, it let anyone form a band, and many did. In 1957, when a 15-year-old Paul McCartney first saw a 16-year-old John Lennon playing a gig at a Village Fete in Liverpool, Lennon wasn’t playing rock and roll, he was playing skiffle. The Rolling Stones, The Who, David Bowie, Led Zeppelin, and many more would all start out in skiffle groups. Let’s take a trip on a freight train down the Rock Island line and explore the phenomenon that was skiffle.

For around 18 months during the mid-1950s, a musical genre with its origins in American blues, jazz, bluegrass, and jug bands would become the catalyst for the start of the British music scene. Post-war England was still trapped in rationing until 1954, a dreary landscape of tradition and shades of grey. The “teenager” hadn’t been invented and the youth were expected to complete school, work or study, then settle down and replicate their parents’ lives. But something was stirring, since the end of the war there had been a baby boom, a rebuilding of the landscape and an economic upturn had meant there was more casual labor for most. What resulted was that young people had means and money in their pockets, and they were going to help invent their own culture. Jazz had been the popular music in Britain since the 1940s, a swinging traditional take on southern African American music; bands played in halls and pubs across the country and this would be where skiffle would manifest itself.

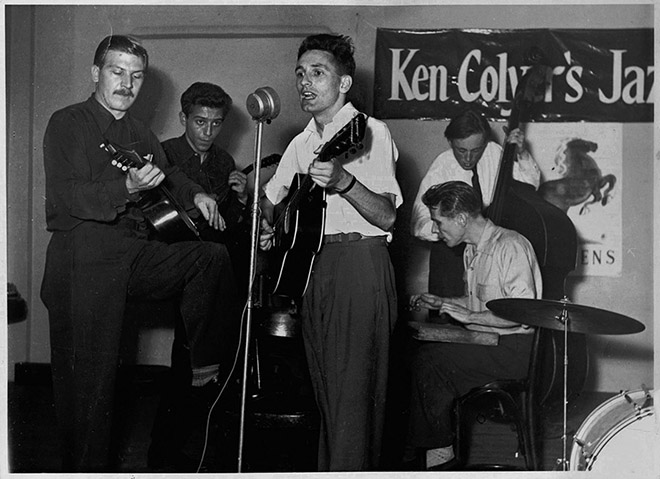

(Pictured) Ken Colyer; Alex Korner; Lonnie Donegan; Bill Colyer and Chris Barber

Ken Coyle was a band leader and trumpet player with the Crane River Jazz Band from West London. He’d been a leading figure in the British jazz scene and exponent of New Orleans sound since he’d actually jumped ship and landed there to play with local musicians. Now he’d formed his own popular ensemble, the Ken Colyer’s Jazzmen which featured Lonnie Donegan on banjo, the musician who would become the most influential artist in skiffle.

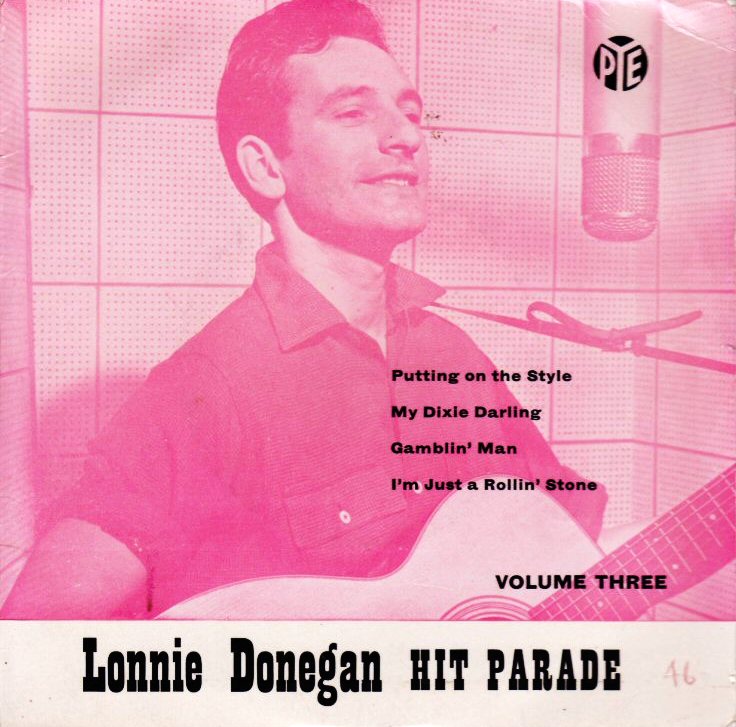

Scottish-born Donegan had grown up in London and he’d learned guitar, become interested in blues and jazz, and played for several bands in the 1940s before he’d be drafted for national service. He’d changed his name to Lonnie in honour of the blues musician Lonnie Johnson. On his return he’d wound up playing banjo for Coyler in his trad jazz band. It was during this period in 1953 that skiffle would be created.

The word skiffle has its origins in African American rent parties, a social phenomenon that began in 1920s Harlem where tenants would essentially raise money to pay their rent by throwing a party. Bands performed to collect money in a hat, usually with improvised instruments, which had been labeled as “Skiffle” music. Many 1920s blues records had also used the title ‘Home town Skiffle’ and ‘Skiffle Blues’

Now Coyler would pluck this appellative out of the air and bestow it on the music that was being created during the breaks in the trad jazz sets. The breaks or the breakdown bands were there to keep the audience engaged while the brass section rested their numb lips. Lonnie Donegan accompanied by a double bass, drummer, and banjo would run through his repertoire of old Lead Belly folk and blues covers. Lead Belly had been discovered serving time in a penitentiary in the 1920s American South by John and Alan Lomax while working for the Library of Congress collecting lost folk music. Donegan had heard these recordings and made his own unique interpretation of those working songs, murder ballads, prison blues, and traditional folk.

The result was a new approach to an older genre. Donegan had realized that trying to emulate something that he hadn’t lived and experienced was spurious. So, they changed the phrasing, raised the tempo, made it swing, rattle, and rock, and Donegan delivered the vocals in a shouting blues bawl. The ‘breaks’ started to become more popular than the main sets.

There was an audience for this new sound and Donegan would be out in the vanguard of the musical transition. Other skiffle groups began to appear on the scene, and nights began popping up in back rooms of pubs in cellars and sheds across London.n 1955, Donegan would release the most important song in skiffle a version of Lead Belly’s Rock Island line. This raced up the charts in the UK and even in America, peaking at number 8, selling over a million copies. It fired on a scattering rhythm and shotgun delivery, a whirling pace that charged into the gangling limbs of the youth, the likes of which had not been heard before in Britain. Skiffle had arrived.

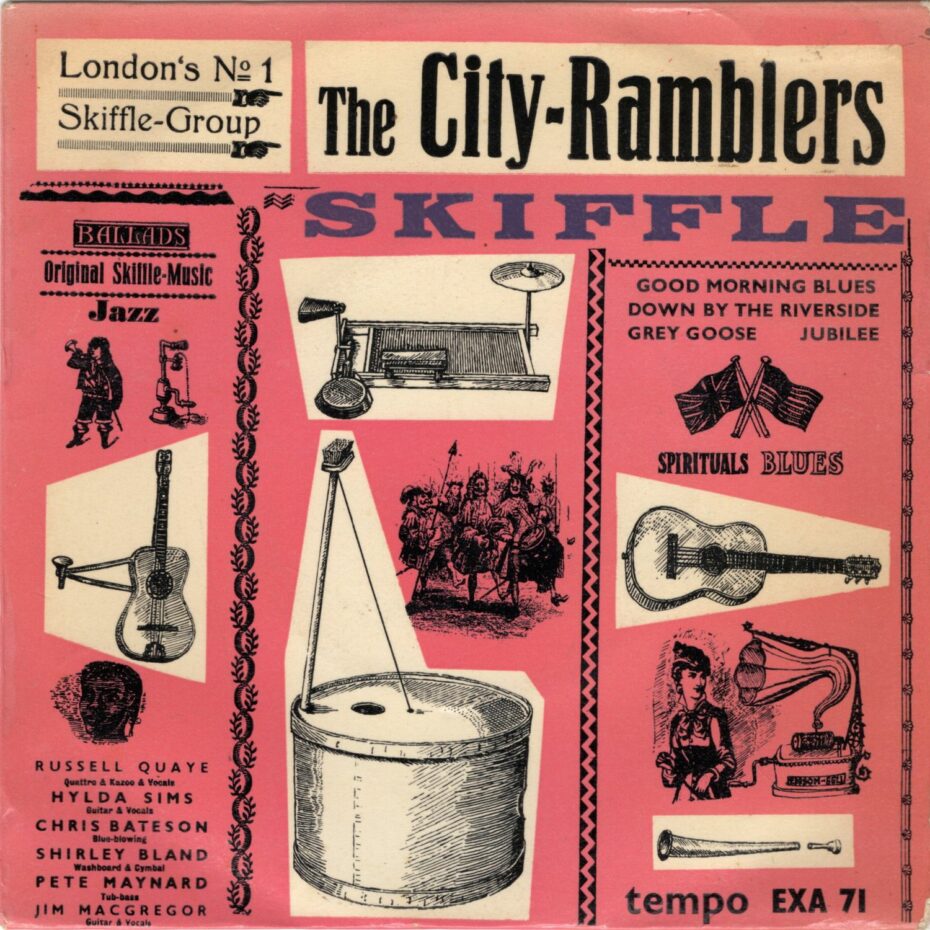

Almost overnight, skiffle bands were formed. It became massive in a relatively short time, not just because of the rousing effect of the music, but because anyone could have a go. You didn’t need to be a proficient musician – you had to know 3 chords, have a guitar, and some household items. For the percussion, a steel washboard usually used for cleaning clothes was now played with a coin or by placing thimbles on the end of fingers to make a scraping, rhythmic beat. For a bass, an old tea chest box was used with an added broom handle and string, to give a plonking sonorous rumble. Add a guitar and an optional kazoo and away you go.